Table of Contents

Having a popular local Singapore dessert - Ice Kachang or Chendol - and you wonder what is thatoval, sweet and translucent white jelly?It is 'attap chee', which means 'attap seed', that comes from the Nipah palm.

aaa

|

comesfrom → |

|

What is it?

General Information

Common namesNipah, Nipah Palm, Water Coconut, Water palmScientific name Nypa fruticans Wurmb. (1779) Etymology (origins of naming) 'Nypa' is the latinised version of the common name 'nipah' that is used in the Philippines and the Moluccas, while 'fruticans' is the Latin word for 'shrubby', which refers to the palm's stemless appearance.[1] SynonymsCocos nypa Lour. (1790), Nipa litoralis Blanco. (1837), Nipa arborescens Wurmb ex H. Wendl. (1878) IUCN Red List status: Least concerned (2010) Status in Singapore: Nationally Vulnerable (2010) [1][2] |

A Quick Scientific Classification Plants Vascular plants Flowering plants Monocotyledons Palms Nipah palm |

- Probably the oldest palm species, with fossil records dating 65-70 million years ago

- Though not the only palm species associated with the mangroves, Nipah palm is the only member in the palm family that constitutes as a major element of mangrove flora

- The Nipah virus, which can cause neurological and respiratory diseases, was named so as the virus’ first human source was isolated in a village by a river full of Nipah palms. The virus is NOT actually transmitted by the palm!

How does it live?

Biology

Natural habitatThis tropical palm grows in areas with warm and humid climate, where temperatures range from a minimum of 20°C to about 32-35°C, and more than 1000mm of monthly rainfall throughout the year. Nipah palm naturally thrives in the soft, muddy substrates of brackish waters and estuarine rivers that have tidal influence which brings in nutrients. It may also be found inland or upstream of rivers on the upper tidal reaches.[3] |

|

||

EcologyPollination of Nipah flowers is by some insects and wind, but mainly by drosophilid flies. Fertilized flowers develop into fruits, forming a large infructescence. When a fruit grows plumule while still on the parent plant, the fruit is pushed away and detached from the infructescence. The fibrous fruit is buoyant and stays afloat on water, and subsequently dispersed by water.[1] |

|

Where can it be found?

Distribution

Natural range

Nypa fruticans is native to South and Southeast Asia, northern Australia and Pacific Islands. It is common in the estuaries and coasts of Indian and Pacific oceans.[1][3]

Globally

Apart from its natural range, the Nipah palm can also be found in West Africa following its introduction in 1906 from the Singapore Botanic Gardens, and have subsequently been found in Panama and Trinidad as well.[1]

In Singapore

The Nipah palm can be found mostly in the Northern coasts of mainland and also on a few offshore islands in the Northeastern and South of Singapore. The map below shows the locations where Nipah populations are found. Although it may seem that the Nipah palms are mostly situated away from the urban city centre, they are still at risk of local extinction if threatened (see Conservation & Management below).

|

| Distribution of the Nipah palm in Singapore. Map © Alex Yee from Teo et al. (2010) |

How to identify a Nipah palm?

Diagnosis/Descriptions

| ====Habit & Structure==== Shrub-like, as named.[4] It differs from other palms in the lack of an upright stem, instead it has underground horizontal stem, known as rhizome, that branches dichotomously. Each new plant grows out from these branches, resulting in an extensive, closely packed Nipah strands. Mature Nipah palms may grow as high as 10m tall. This height is contributed by the palm leaves growing upwards in a rosette pattern from the ground surface.[3] |

|

||||||

| ====Leaves==== Each stiff, erect leaf may extend up to 9m long. Leaves are pinnate with long, alternating leaflets branching out from the main leaf stalk. These leaflets may be 60 to 130cm long and numerous in number at 30 to 40 leaflets per leaf. The upper leaf blades are shiny green and the lower surface may be powdery. The leaf bases overlap below ground, although these may be exposed by erosion of the substrate over time.[1][3] |

|

||||||

| ====Inflorescence==== The Nipah palm has both female and male flowers on the same plant. These yellow inflorescence arise from sturdy 1m long stalks from the base of the palm. The inflorescence are dimorphic - the female flowers are arranged into a round, golf-sized ball at the tip of the central stalk, while the much smaller male flowers are closely packed into a club-shaped spike branching from the central stalk.[3] |

|

||||||

| ====Fruit & Seed==== Similar to the female flowers, the Nipah fruits are arranged in a spherical bunch that can be 30-45cm in diameter. Each angular fruit is fibrous and chestnut-brown, ranging from 10-15cm long and 5-8cm wide. As the fruits mature, the stalk supporting the fruit bunch often droops due to the weight (see photo on the left), but it may be held up by incoming seawater in areas with tidal influence. Within each fruit, an egg-shaped seed with soft, edible endosperm is contained.[1][3] |

|

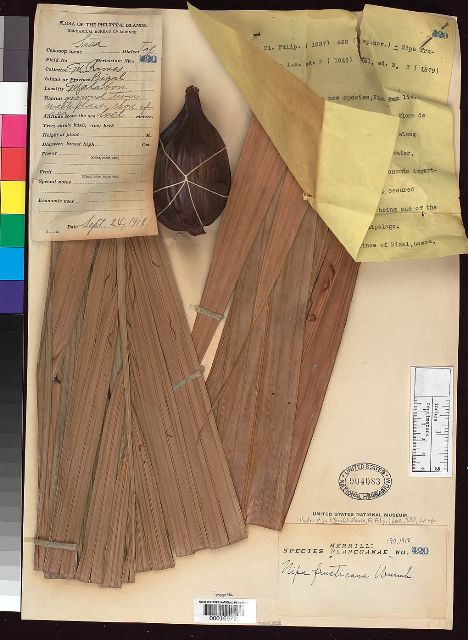

Type Information

The Nypa fruticans holotype specimen can be found at the US National Herbarium (barcode 00016972).

One may refer to this model specimen to confirm the identity of the Nipah palm.

|

Why is this plant so important to us?

Economical Importance

The Nipah palm is one of the most heavily utilised mangrove species in the world! Have you come across these uses [5] before?Nutritional value

| Attap Chee The soft endosperms of young Nipah seeds are a delicacy in the tropical regions. These are often preserved in syrup and they make a popular dessert ingredient in Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia.

Spice Salt can even be extracted from the stems and petioles of the Nipah palm. |

Beverages/Vinegar The sugary sap from the inflorescence and stalk can be used to make alcoholic beverage commonly known as 'toddy' in some parts of South and Southeast Asia. It can also be used to make vinegar.

Traditional medicines The young shoots, burned roots and leaves or the decayed wood of Nipah have been used to make traditional remedies for toothache, headache and even herpes. |

Household materials/products

| Roof thatching Traditionally, the leaves of the Nipah palm have been harvested for roof thatching and wall material. Mature Nipah leaves are dried and the midribs are removed.The leaves are folded over a main rod of bamboo or wood and placed overlapping the adjacent leaves before stitching them tight. These roofing material may last for 5 years or more. A commercial market for such roof thatching has even developed in the 1980s. |

|

||

| Brooms Locally known as 'sapu lidi' in Indonesia, it is a common household item made from the dried midribs of the Nipah leaflets. Apart from using the 'twig broom' to sweep the floor, it can also be used to remove dust on mattresses.This is done by hitting the mattress repeatedly with the broom to let the dust disperse into the air.

|

Firewood Parts of the Nipah palm that are unused for other functions are used as a source of fuel-wood for fire in many villages. Biofuel Sparked by the rising cost of fossil fuels, an interest in ethanol for fuel from the sugary palm sap began as early as the 1910s in the Philippines.[5] In Malaysia, the potential of Nipah ethanol as biofuel is high and companies hope to produce over 6 million litres of Nipah ethanol per year.[9] |

||

| Handicrafts In many Malaysian villages, locals are still actively making traditional bowls or containers, mats, hats, bags or even umbrellas using the dried midribs of palms. These are often sold as handicrafts for livelihood. The hardened mature seeds are used as buttons too! |

|

Pig feed

The Nipah sap is fed to pigs in some islands of Indonesia, as it is known to make the pork meat taste sweeter. [3]

Ecological importance

Coastal protection

The Nipah palms' unique horizontal rhizomes growing underground can help to stabilize coastal areas and river banks, this protecting the land-water margins from erosion by oncoming water and waves. Similar to mangroves, Nipah palms growing along the coastlines act as buffer regions, absorbing the impact of oncoming waves or storms and strong winds.[6] In fact, they are important components of land progression (coastline extension) as they retain silt and sediments[6] deposited by the surrounding waters.Habitat for other organisms

The Nipah palm population is home to a community of organisms. These includes the African mud crab (Panopeus africanus), stone crab (Menhippe nodifrons), mangrove oyster (Crassostrea gasar)[7], and the edible mud mussels (Geloina coaxans)[3]. The Nipah mangrove areas are also important hiding and spawning grounds for many other marine organisms.All in all, the Nipah mangroves contributes to increased species richness through habitat heterogeneity.[8] Maintaining species richness is especially important in Singapore since it is a biodiversity hotspot.

| Nipah palms along the coast act as buffer against strong waves and stabilize the shoreline. Photo © Erika I. Halim |

What can we do to protect this treasure?

Conservation & Management

Since Singapore's independence in 1965, rapid urbanization have caused the loss of as much as 90% of the original mangrove-covered area.[8] As such it is crucial that we protect the mangroves of this sunny island. One of such mangrove species, the Nipah palm is a native plant species in Singapore. Recently it has been classified as nationally endangered in Singapore.

Threats

In Singapore, the main threat to the Nipah palm populations today is habitat loss or destruction.[1] This is due to land reclamation, land use change such as making way for the construction of housing estates and even for waste disposal sites as in Pulau Semakau, or the creation of artificial seawalls to stabilize coastlines. Pollution from organic wastes or oil from shipyards and petroleum-based industries, especially in Singapore where it is a petro-chemical hub, is also a serious problem.[6]Management in Singapore

Protected nature reservesNipah palm populations at the Sungei Buloh Nature Reserve, Pulau Ubin (offshore rural recreation spot) and Pulau Tekong (military training grounds) are protected, although reclamation activities are currently ongoing in Pulau Tekong and this may have adverse effects on the Nipah palm populations there. On the other hand, the wild populations in various parks across Singapore such as Admilralty Park and Pasir Ris Park are relatively safe from future human developments. In addition, there have also been plans to gazette the Berlayar Creek and Lim Chu Kang mangrove regions as protected areas in the near future[1] -- this is good news for our Nipah palms!

Replanting

The Nipah palm has been successfully cultivated in freshwater at Singapore Botanic Gardens' Eco-Lake[1], suggesting its replanting suitability. In other regions such as Malaysia, Nipah palm seedlings have proven to thrive well after replanting along river banks[10]. Following the pressing threats to Singapore's Nipah populations, we can look into replanting them in other areas safe from habitat alterations.

| Education The National Parks Board (NParks) have actively been educating the public about Nipah palm and other common native species that can be found around Singapore through description boards erected along trails in parks and nature reserves. Such information help to increase awareness of the existence of such species, its role in the ecosystem, and its practical uses for humankind. Only when the general public is aware that these plant species is of such importance to them, will they want to protect it and take actions. |

Individual responsibility

In Singapore, every resident is encouraged to be responsible for their own environment. No action is too small to make a difference on our planet.

So here are two simple tips for protecting our mangroves:

- When visiting parks or nature reserves, take nothing but photographs and leave nothing but your footprints!

- Be actively aware of environmental issues and get involved in conservation activities - you can start by volunteering in mangrove cleanup activities.

Remember, without the Nipah palm, we will not have that sweet, translucent white jelly in our Ice Kachang anymore!

| Nipah along mangrove boardwalk at northeast Pulau Ubin, a popular eco-tourist spot. Shouldn't we conserve such beautiful trails? Photo © Erika I. Halim |

Glossary of terms

| Dichotomous |

Branches into two parts |

Midrib |

The middle vein of a leaf |

| Dimorphic |

Occurrence in two distinct forms |

Monocotyledons |

Plants that produce seeds with a single cotyledon (the primary leaf of the embryo of seed plants) |

| Endosperm |

The nutritive material in seed plant ovules, usually surrounding the actual seed |

Native species |

Species that are endemic to the area in relation |

| Habit |

(Botany) The form in which a plant grows |

Petiole |

The stalk which attaches the leaf blade to the main stem of a plant |

| Habitat heterogeneity |

Variatons of environmental conditions within a particular habitat |

Plumule |

The shoot that first grew out of the embryo in germinating seeds |

| Holotype specimen |

The type specimen from which the species description is obtained |

Synonym |

Other scientific names that refer to the same species |

| Inflorescence |

A cluster of flowers; flowers collectively |

Type information |

The exact individual specimen from which the species description is obtained for reference |

| Infructescence |

The fruiting stage of inflorescence |

Vascular plants |

Plants with vascular system (having a system of vessels that conduct fluid to different parts of the plant) |

References & Links

Other online pages on the Nipah palm can be found at these links:

http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/plants/mangrove/nypa/nypa.htm

http://www.naturia.per.sg/buloh/plants/palm_nipah.htm

http://mangrove.nus.edu.sg/guidebooks/text/1068.htm

1: Teo, S., Ang, W. F., Lok, A. F. S. L., Kurukulasuriya, B. R., & Tan, H. T. W. (2010). The status and distribution of the nipah palm, Nypa fruticans Wurmb (Arecaceae), in Singapore. Nature in Singapore. 3: 45-52.

2: NParks Flora and Fauna Web online at https://florafaunaweb.nparks.gov.sg/Special-Pages/plant-detail.aspx?id=2658

3: Lim, T. K. (2012). Nypa fruticans. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants (pp. 402-406). Springer Netherlands.

4: Moore Jr, H. E., & Uhl, N. W. (1973). Palms and the origin and evolution of monocotyledons. Quarterly Review of Biology, 414-436.

5: Hamilton, L. S., & Murphy, D. H. (1988). Use and management of nipa palm (Nypa fruticans, Arecaceae): a review. Economic Botany, 42(2), 206-213.

6: Hsiang, L. L. (2000). Mangrove conservation in Singapore: A physical or a psychological impossibility?. Biodiversity & Conservation, 9(3), 309-332.

7: Udoidiong, O. M., & Ekwu, A. O. (2011). Nipa Palm (Nypa fruticans Wurmb) and the Intertidal Epibenthic Macrofauna East of the Imo River Estuary, Nigeria.World Applied Sciences Journal, 14(9), 1320-1330.

8: Yee, A. T. K., Ang, W. F., Teo, S., Liew, S. C., & Tan, H. T. W. (2010). The present extent of mangrove forests in Singapore. Nature in Singapore, 3, 139-145.

9: Online article 'Malaysian company thinks it can produce 6.48 billion liters of ethanol from Nipah' at http://news.mongabay.com/bioenergy/2007/04/malaysian-company-thinks-it-can-produce.html

10: Personal experience from a volunteering activity with World Wildlife Fund (WWF) at Terengganu, Malaysia in May 2013.